The truth about Putin’s shootdown

Investigating MH17, the crime that presaged the war in Ukraine

The fields of Hrabove bloom yellow in the summertime. On July 17th 2014 Vitaly rose at 6am, walked out of his front door and pushed past rusted gates on which his young daughter had drawn mermaids in chalk. He trudged down a dirt road, past rows of sunflowers. He roused a herd of cattle, 22 in total, and drove them out to graze. It was a beautiful day.

As a boy, Vitaly dreamed of becoming an astronaut. But he was a poor student, and never ventured far from home. His life mostly revolved around Hrabove, an eastern Ukrainian village frozen in Soviet amber. Vitaly had never visited Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital, nor flown on a plane, much less a space shuttle. His world—the green expanse from the chicken coop to the reservoir—was small and peaceful. Until that summer.

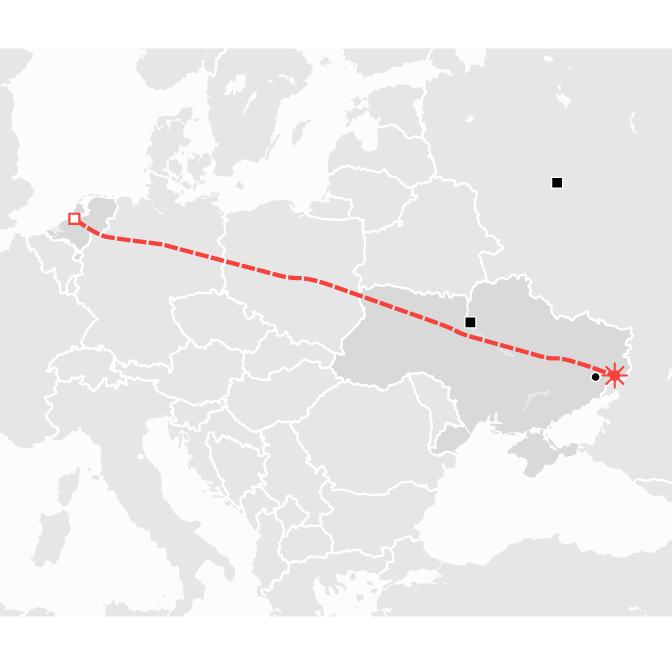

The path of Malaysia Airlines flight 17

Moscow

Amsterdam

POLAND

BELARUS

RUSSIA

GERMANY

Kyiv

UKRAINE

Donetsk

HUNGARY

ITALY

ROMANIA

Crimea

SERBIA

BULGARIA

TURKEY

Source: News reports

Just before 7am that day in Rotterdam, 2,500km away, Silene Fredriksz opened the door to her son’s room. Bryce and his girlfriend, Daisy Oehlers, had to catch a flight to Kuala Lumpur, and then on to Bali. Bryce, whose father, Rob, is Indonesian, wanted to show Daisy his second home. She hoped to reset after losing her mother to cancer. “Heading to paradise,” she told friends. When Ms Fredriksz entered, Bryce, 23, a young man who aspired to play professional football, was still lazing in bed; Daisy, 20, who wanted to be a schoolteacher, was about to take a shower. She hugged them both. “Yeah Mom,” Bryce said. “No problem, we’ll take care of each other, we’ll have fun, don’t worry.”

Michaël Niewold’s younger brother, Tallander, was also excited about Bali. He planned to climb a volcano there. Tallander, 22, a soldier, had just been promoted to private first class. Mr Niewold gave “Tallie” a call after finishing an early shift at the Dutch news channel where he works, and caught him at the airport. “Have a good journey,” he told his little brother.

Bryce, Daisy, Tallander and 295 others boarded Malaysia Airlines Flight 17. The young couple buckled in to row 17, seats D and E; Tallander took his place just in front of them, 16D. The plane took off at 12:31pm for what should have been a routine trip. At around 3pm, MH17 radioed a control tower in central Ukraine. Then it continued flying over Donbas, where for several months Russia and its separatist proxies had been fighting a war against the Ukrainian government.

Vitaly was herding his cows. He heard a bang, looked up and saw a plane. It kept getting bigger and bigger, as if flying towards him, spinning wildly and then breaking apart. “No freaking way,” he thought. He hid in a ditch, covered his head with his backpack and prayed. The crash shook the earth. With fragments still falling, Vitaly ran towards the road, where he saw one body, undressed, lying face down, and soon another. He found corpses in civilian clothes strapped into their seats, and realised it must have been a passenger plane. He went home, where his mother and daughter were hiding in the basement. His father had gone out to look for him. When they finally found each other, they hugged.

Your correspondent happened to be in eastern Ukraine that day, covering the war. He arrived in Hrabove as dusk fell, after driving past hardscrabble towns, coal mines and smoky factories, through checkpoints manned by scraggly separatist soldiers. He found the fields filled with mangled bodies, charred metal and the eerie debris of arrested lives: guidebooks and playing cards, Kleenex packs and Maxi pads, a stuffed pink horse and a real blue Macaw, an orange bikini, a melted necklace and a watch frozen at 3:27.

“Only a lobotomy could make me forget this,” Vitaly’s father, Viktor, said that night, sipping what he called his first glass of vodka after eight years of sobriety. “What words could possibly explain this? Let this world degenerate and let the dinosaurs roam again—at least they did not go around killing each other with weapons like this. We have become beasts.”

The news reached Mr Niewold when he was at home, watching the Tour de France. He saw reports of a plane crash. The information looked ominous: a Malaysia Airlines flight to Kuala Lumpur that had departed from Amsterdam. He phoned his parents. “I think this is very bad news,” he told them. Ms Fredriksz received a similar call from her husband. “No!” she replied. “No, it’s impossible, it can’t be true.”

As soon as MH17 came crashing down, a battle for truth and accountability began. Western and Ukrainian officials said that a surface-to-air missile fired from separatist-held territory had caused the crash. Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, who at the time denied any involvement in the conflict in eastern Ukraine, blamed the authorities in Kyiv.

For a moment, the tragedy seemed like it might galvanise global action to end the then-nascent war in Ukraine. Many Ukrainians thought it would shock the world into helping. Barack Obama, then America’s president, said it would “be a wake-up call for Europe and the world that there are consequences to an escalating conflict in eastern Ukraine”.

What followed, however, were limp sanctions, a poisoned peace agreement between Ukraine and Russia in early 2015, and a return, largely, to business as usual between Russia and Europe. Germany launched Nord Stream 2, a new gas pipeline, a year after the crash; football fans descended on Moscow for the World Cup in 2018. Only when Vladimir Putin openly invaded Ukraine in 2022 did the world truly wake up. And yet, as the open war drags into its third year, some are falling asleep again, forgetting what is at stake in the sunflower fields of eastern Ukraine.

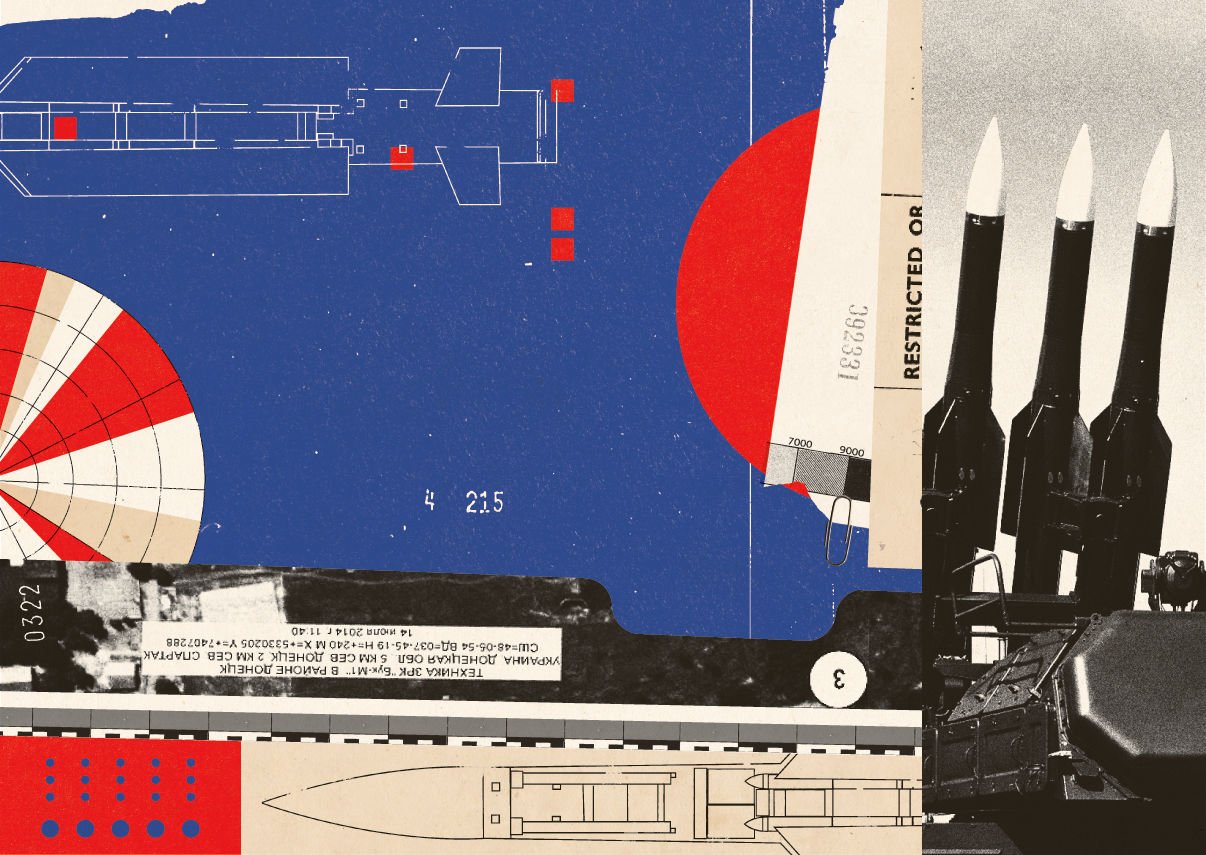

Image: Cristiana Couceiro

As it became clear a passenger plane had crashed, Igor Girkin knew he had a mess on his hands. A veteran Russian soldier and spy, the mustachioed Mr Girkin went by the call sign “Strelkov”, or “The Shooter”. Since his student days, he had campaigned for the restoration of the Russian empire. He abetted Russia’s annexation of Crimea and later emerged as “defence minister” of the Donetsk People’s Republic, a Russian puppet statelet illegally carved out of eastern Ukraine. He had been pleading with contacts in Russia for “decent anti-aircraft defence” to counter the Ukrainian air force, as he put it in an intercepted phone call.

On the morning of July 17th Mr Girkin gathered his commanders at his headquarters. A Buk surface-to-air missile system had finally arrived from Russia. That afternoon, a social-media page believed to be operated by Mr Girkin’s supporters posted a triumphant dispatch about downing a Ukrainian military plane near Snizhne, a city next to Hrabove, only to edit it soon after. Sergey Dubinsky, one of Mr Girkin’s deputies, tried to persuade his boss that a Ukrainian fighter jet had shot down MH17. Mr Girkin was sceptical. He pressed Mr Dubinsky to make sure “the equipment” made it back to Russia. Lest they appear to be engaged in a cover-up, the separatists allowed international officials and investigators access to the 50km2 crash site to recover the remnants of the plane.

Russia could simply have confessed to what was probably a tragic mistake, as other countries have in the past. America hit an Iranian passenger jet in 1988, killing 290; Iran fired on a Ukrainian one in 2020, killing 176. Both governments ultimately took responsibility. Some Russians wanted to do the same—Novaya Gazeta, an independent newspaper, put MH17 on its front page, with the words “Forgive us, Holland.” But Mr Putin instead embarked upon a campaign of lies.

The aim was not to convince people of any specific version of events, but to confuse them and make them doubt that the truth was knowable. Russian media said a Ukrainian fighter shot down MH17, pointing to a Twitter account purporting to belong to a Spanish air-traffic controller named Carlos working in Kyiv who saw Ukrainian aircraft on his radar. (A Spanish ex-convict later told journalists he was paid by Russian sources to write the messages.) Some pundits blamed the CIA. Russian media ran reports that the bodies on the plane appeared to have been dead before the crash. In late 2014 Mr Girkin mused that Ukraine organised the crash “as a massive provocation”.

Meanwhile, funerals had to be organised, often more than once, as many bodies came back in pieces. Bryce was identified via a charred right foot. Daisy returned home as an 18cm-long pelvic fragment.

Amid the grief, many next of kin placed their faith in the justice system to deliver answers. Yet they also knew they were unlikely ever to see the perpetrators behind bars. “It’s not like they’re looked for by the FBI—it’s just the Dutch, with all due respect, public prosecutor,” Mr Niewold reflected in 2015.

The news about MH17 reached Digna van Boetzelaer while she was on holiday in Bali. Just a week earlier, she and her daughter had flown the same route as many of the passengers on board had planned to. Her daughter came running towards her in a panic: one of her school friends had been on the plane. Many people had a connection to the tragedy. As a share of the population, more Dutch died on that flight than Americans in the 9/11 attacks. Ms Van Boetzelaer, a prosecutor, volunteered for the MH17 criminal trial. She had the right name for the job: Digna, as in dignity.

Digital sleuths from Bellingcat, an investigative journalism outfit, had pieced together social-media posts to trace the route of a Buk missile system from a base in Russia to separatist territory in eastern Ukraine, suggesting that Russia supplied the deadly weapon. Yet making that case stand up in court was another matter. The Dutch Safety Board first reconstructed the wreckage of the plane at an airbase in southern Holland. Distinctive butterfly-shaped shrapnel inside the pilots’ bodies told them that the missile in question was a Buk. A Joint Investigative Team (JIT) set up by Australia, Belgium, Malaysia, the Netherlands and Ukraine spent years gathering evidence into the Buk’s provenance and chain of command.

Several legal cases were launched, including interstate trials between Ukraine and Russia at the European Court of Human Rights and the International Court of Justice, a UN body. But Dutch prosecutors, led by the JIT, focused on the most vexing questions of individual criminal responsibility. In the summer of 2019, they announced murder charges against three Russians and one Ukrainian: Mr Girkin, Mr Dubinsky, and two of their deputies, Oleg Pulatov and Leonid Kharchenko. Since Russia does not extradite, the suspects were tried in absentia. But Ms Van Boetzelaer held on to hope that eventually they might face justice.

Over years of hearings the JIT team steadily built their case. Investigators had painstakingly cross-referenced and verified images and videos, often seeking out the original cameras or memory cards that captured crucial stages of the Buk’s journey. Dozens of first-hand witnesses, including separatist fighters positioned near the missile launch site and involved in escorting the Buk out of Ukraine after the crash, gave secret testimony, despite the dangers involved.

Yet as the trial unfolded, the accused were unruffled. In mobile-phone footage from 2019, Mr Dubinsky can be seen drinking with another separatist commander on a boat in Crimea, toasting Mr Girkin, who had become a prominent nationalist activist back in Moscow, pressing for Russia to finish what it started in 2014. No wonder, then, that Mr Putin felt emboldened. As Roman Liubyi, the director of “Iron Butterflies”, a documentary about the disaster, puts it, if you can shoot down a passenger plane with impunity, you “can invade the country next to you, no problem”.

Image: Cristiana Couceiro

On November 17th 2022, eight years and four months after the crash, relatives, lawyers and journalists packed the courtroom to hear a verdict. MH17, the judges declared, had indeed been downed by a Buk fired from separatist-controlled territory and delivered from Russia. Messrs Girkin, Dubinsky and Kharchenko bore criminal responsibility for the death of the 298 people aboard; Mr Pulatov, a lower-ranking operative, did not. Russia, the judges said, had been a party to the conflict since 2014, despite its denials. In the courtroom, relatives embraced.

“Two key words were very important for me: Russia and murder,” Ms Fredriksz said. “It’s a relief.” For Mr Niewold, the acquittal of one of the defendants made the decision even more powerful. “It showed we have an independent judicial system,” he said, allowing himself a rare smile. Ms Van Boetzelaer sighed with satisfaction: “For the next of kin, they now know all those facts have been confirmed by a court.”

Yet the perpetrators remain at large and missiles are still flying across Ukraine. “Holding to account masterminds is crucial too,” said Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, after the verdict. The JIT officially concluded its work in February 2023. At the final public presentation, investigators played intercepted conversations featuring Mr Putin which suggested he might have personally approved the Buk’s transfer to eastern Ukraine in 2014. But the evidence needed to prosecute remains out of reach. “We know that the answers to our questions can be found in Russia,” declared Ms Van Boetzelaer. They will not be found until the skies over Hrabove, Kyiv and all of Ukraine are peaceful again. ■

Photos: Getty Images