East Asia’s new family portrait

Households across the region look very different from previous generations. Governments are struggling to keep up

|

CHIBA, GUANGZHOU, SEOUL and TAOYUAN

Xu Zaozao of Guangzhou was 30 years old when she broke up with her then-boyfriend in 2018. Though she felt social pressure to settle down and start a family, she did not want to put her career on hold. “In the background there's a lot of the past era’s family values,” she says, but “there were so many ideas I had that I hadn’t realised yet.”

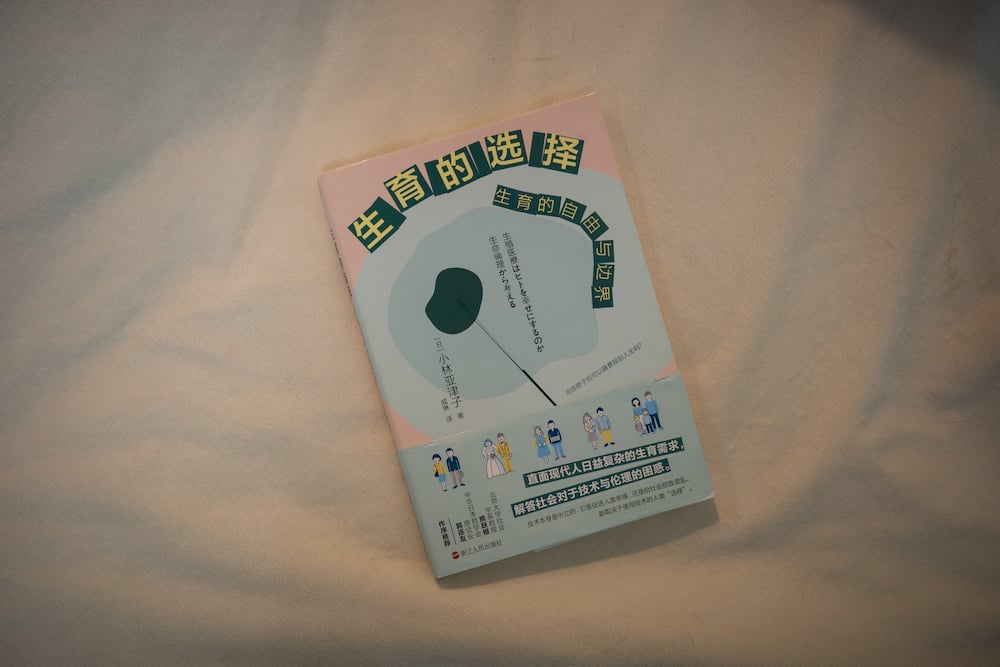

She hoped to preserve her ability to have children in the future by freezing her eggs. But doctors at the Beijing hospital she visited denied her request, as Chinese law allows only married couples to do so. Instead they urged her to marry and get pregnant earlier. Undeterred, she sued the hospital in 2019 for discriminating against women and violating her rights. In 2022 a court ruled in favour of the hospital, but Ms Xu (pictured below) has appealed.

She is still hopeful of a change to Chinese regulations, which she sees as linked to negative stereotypes about single mothers. “I really wish everyone could see a more authentic and more diverse image of women who are single and want to have children,” she says. Her case has become a cause célèbre, galvanising support from tens of thousands of followers on social media, many of them women in their late twenties or early thirties. “Should we neglect a whole generation of single women’s demands just because we can’t update this policy?”

Ms Xu’s experience is illustrative of broader trends happening throughout East Asia. For her parents’ generation, households in China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan largely consisted of mono-ethnic married couples with children, where men worked and women kept the home, an arrangement with its underpinnings in widely shared Confucian values. While traditional families remain widespread, families across the region are becoming far more varied. As young people delay or eschew marriage and having children, nuclear families are in decline: in Japan, where this process began earliest, couples with at least one child accounted for 42% of households in 1980, when single-person households made up just 20%; by 2020, couples with children had fallen to 25% of households, and single people accounted for 38%. In East Asia today, “the diversification of household structures is the story,” says Paul Chang, a sociologist at Harvard University.

Yet in much of East Asia, laws and social mores around marriage and family are lagging behind the new reality. Instead of working to revise and reform them, governments have responded mostly by offering financial incentives to marry and have children, in the hope of reviving the traditional family. The nuclear family is failing East Asia, which seeks to reverse a demographic decline. The answer is not to strengthen its legal, social and cultural monopoly, but to remove the obstacles that make it so hard to raise children in other settings. Many people are already trying to do so, as the four path-breaking families profiled here demonstrate.

Family life has big implications for the region’s demographic profile, and in turn, for its economic power. Ultra-low birth rates and stiff resistance to immigration produce shrinking populations: according to the United Nations, the four East Asian territories will see their combined populations shrink by 28% between 2020 and 2075. During the same period, their combined share of global GDP is projected to drop from 26.7% to 17.4%, according to Goldman Sachs, a bank.

No wonder, then, that political leaders see families as an urgent policy priority. Xi Jinping, China’s leader, has promised “a national policy system to boost birth rates” and launched a national effort to promote “new-era marriage culture”. Japan’s low birth rate leaves it “on the brink of whether it can continue to function as a society”, according to its prime minister, Kishida Fumio, whose government launched a new “Children and Families Agency” in April. In March at the inaugural meeting of a new government body focused on the challenge, Yoon Suk-yeol, South Korea’s president, called his country’s birth rate a “crucial national agenda” in need of an “emergency mindset”. Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, has called its declining birth rate a “national-security problem” and pledged government support to make everyone “willing to marry, daring to have children, and happy to care for the old."

As in much of the world, industrialisation and urbanisation in East Asia in the 20th century fuelled a shift away from extended multi-generational households towards nuclear families. At the same time, governments pushed family-planning policies that, ironically from today’s vantage-point, sought to reduce the number of children being born. In South Korea, for example, men in the 1970s could receive preferences in housing lotteries and exemptions from military-reserve training if they had vasectomies. China went the furthest, as its government suppressed fertility artificially through the infamous one-child policy, implemented patchily from 1980 to 2016. (China replaced the one-child policy with a two-child policy in 2016, and then a three-child policy in 2021.)

The average size of households has been falling across the region for decades. In Taiwan nuclear families accounted for 47% of households in 2001, while single and childless families made up just 24%; by 2021, the share of single and childless families had risen to 34%, while nuclear families had dropped to 33%. In South Korea single-person households accounted for 4.8% of households in 1980; by 2021 single-person households accounted for 33.4% of the total, a historic high. In China 8.3% of households in 2000 had just one person; by 2020, the ratio had increased to 25.4%.

Ever more young people across the region are marrying later or skipping marriage entirely. China registered 6.8m marriages in 2022, the lowest number since data became available in 1985, and roughly half the peak of 13.5m in 2013. South Korea saw 192,000 marriages the same year, the lowest number since 1970, when data there began being gathered. In Taiwan there were 125,000 new marriages, a 30% drop from the peak in 2000. In Japan 504,878 couples tied the knot, a slight increase from the previous year, but still amongst the lowest levels since the second world war.

Many have decided not to have babies either. Children, once seen as essential, have become optional. Japan’s fertility rate (the number of children an average woman can expect to bear in her lifetime) began to decline in the late 1970s and hit a record low of 1.26 in 2022, as the number of new births dipped below 800,000 for the first time since records began in 1899. In China, too, the population last year shrank for the first time since 1961, as the fertility rate fell under 1.2. That still places it ahead of South Korea, which set a world record for the lowest fertility rate in 2022, at just 0.78, and Taiwan, where the fertility rate was just 0.87. More new pets (230,000) were registered in the self-governing territory last year than children were born (140,000); some Taiwanese have taken to calling their critters “fur children”.

Variation between families is growing in myriad other ways. “The idea of the homogeneity of the family is being shaken,” says Nishino Michiko, a Japanese sociologist. Cohabitation before marriage, once a taboo in much of the region, has become more acceptable. Gay people and single parents are clamouring for the legal rights to form families and have children. Two-income households have become more common, as have divorces and remarriages. Ageing has also altered family dynamics. In Japan, where people over 65 years old account for nearly 30% of the population, a new lexicon has emerged: “80-50” and “90-60” families are those consisting of an elderly parent living with a middle-aged child.

Taiwan has gone furthest in redefining who can officially be considered a family. It legalised gay marriage in 2019 and in May of this year made it legal for same-sex couples to adopt children. In recent years it has also moved towards greater integration of migrants, redefining the Taiwanese family to include multicultural ones. In 2022 the number of marriage migrants, mostly from China and South-East Asia, was 577,900, about 2.5% of Taiwan’s total population.

Growing up in Taoyuan, a city in Taiwan’s north-west, Tsou Chia-ching, whose father is Taiwanese and mother is from the Philippines, often saw television reporters discussing foreign brides’ potential to run away and the danger of giving them money or passports. They spoke as if the women were “objects, not humans”, says Ms Tsou, now 26. At school she did not talk about the Filipino side of her family. Neighbours and even some relatives bullied her mother.

More recently, Taiwan’s president, Ms Tsai, began promoting multiculturalism, in part as a political move to distinguish Taiwan from China. Ms Tsou (pictured with her family below) has been invited to speak frequently at events celebrating South-East Asian cultures. She was asked to serve on a government committee for new immigrants. In 2020 she opened a Philippine restaurant with her parents, attracting Taiwanese customers whose questions about the Philippines were no longer centred on the “foreign bride” stereotypes of the past. Ms Tsou’s brother, ten years younger than her, has not experienced any of the discrimination she faced in school. “Isn’t it normal to have many classmates with parents from different countries?” he shrugs when Ms Tsou asks about what it’s like for him to be half-Filipino. His nonchalance shows just how far Taiwan has come, she says.

In some respects, the trends resemble those that swept rich Western countries from the 1970s onwards, a phenomenon sociologists dubbed the “second demographic transition”. But different forces are at work in East Asia, Mr Chang of Harvard argues: “The changes are driven by anxieties, social problems and social conflicts,” not the triumph of the individual. In the OECD, a club mainly of rich countries, more than 40% of children are now born out of wedlock, while in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan the share is less than 5%. (China does not keep official data and makes it difficult to register and receive benefits for such children.) Falling fertility rates across East Asia are thus largely the result of the decline of marriage. In Japan, for example, the fertility rate of married women was 1.9 in 2022, down only slightly from 2.2 in 1971.

Economic precarity is one big reason for the decline of traditional families in East Asia. In surveys, many still say they want to get married and even have a number of children. But more and more of them feel they cannot afford to do so. High education and housing costs make having children a luxury. Many men, especially those with more precarious jobs, fear they cannot provide enough to make a marriage work. “Marriage and family are becoming this thing you achieve if you can afford it,” says Mary Brinton of Harvard University.

But money is at best only part of the story. Institutional and cultural rigidity are also making it difficult for young people to form new families. Changes to patterns of marriage and childbearing in East Asia largely emerge from the tension between rapid social and economic change and the unchanging structure of marriage and family relations, argues James Raymo of Princeton University.

Even as women’s education levels have risen, traditional gender roles still pervade the home, where women are expected to perform all the “feminine work” of cleaning, cooking, child care and care for the elderly. Though a growing number of men in East Asia take paternity leave, they are still in a minority. Long working hours and inflexible corporate cultures make balancing work and family even more difficult than elsewhere in the world, raising the opportunity cost of marriage for many women. “Women’s status is rising and society cannot keep up with that,” says Alice Cheng, sociologist at Academia Sinica, a Taiwanese research institute. Many women are thus deciding to reject marriage altogether. Wang Feng, a demographer at the University of California Irvine, calls it East Asia’s “quiet gender revolution”.

The backlash has become most pronounced in South Korea, breaking out into what some commentators call a “gender war”. In the summer of 2018, inspired by the #MeToo movement, thousands of women took to the streets to protest against so-called “molka” videos, or spy-cams that are hidden in public toilets, changing rooms, offices and shoes, with the footage then posted to the internet. That in turn spawned the “tal-corset” (free the corset) movement, which encourages women to cut their hair and throw out their make-up. Women have also taken to vowing to never get married, declaring themselves “bihon” (willingly unmarried).

Lee Min-gyeong always wanted to provide for her family. Now a 30-year-old writer and activist, Ms Lee was asked when she was in primary school about her dream job. She jotted down: “head of the household”. Yet as a young woman in patriarchal South Korea, it seemed impossible. “How can you be a breadwinner when you live with a man?” she wondered.

After she came out as a lesbian in 2020, Ms Lee decided to start a family of a different kind. Gay marriage remains illegal in South Korea, so she created a company, Guerrilla, whose members (pictured below) live and work together. The enterprise consists of a school that teaches women language, writing and finances; a property business that rents out space for women; a talent-management company for female artists; and a women’s shelter. “This is what Guerrilla is about: Fighting the patriarchy by protecting, educating and investing in women," Ms Lee declares.

Guerrilla has since grown into a family of seven, including Ms Lee’s partner, their adopted daughter (who is just two years younger than Ms Lee), another couple, a friend and a dog. “I wanted to show the world that you don’t have to be blood-related, but you can become a family just with intellectual connections,” Ms Lee says.

Policymakers want today’s youth to marry and procreate more. But their ideas for encouraging this consist mostly of economic incentives. Taiwan’s government has offered subsidies and cash prizes for child-bearing. China has set up 32 “national marriage custom reform experiment zones”, with expedited marriage registration, marriage-counselling, and cost-saving group weddings. Mr Yoon, the South Korean president, admitted in March that the 280trn won ($215 bn) spent over the past 16 years to halt demographic decline has made little difference, but that has not stopped the government from talking about throwing more money at the problem. In Japan, Mr Kishida has promised to spend an additional ¥3.5trn ($25bn) annually over the next three years on children and family support measures.

At the same time, many (male) leaders are also reinforcing traditionalism. Mr Xi has promoted a revival of Confucianism, which upholds traditional gender roles, as a part of China’s path to “national rejuvenation”. The Communist Party has censored feminist and LGBT groups and arrested some of their most prominent activists. Local officials have given lectures on filial piety and the importance of family.

Under Mr Yoon’s progressive predecessor, Moon Jae-in, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family extended its definition of a “family” eligible to receive social benefits beyond married heterosexual couples to include unmarried couples, single parents and even same-sex couples. Mr Yoon has walked those steps back and vowed to abolish the ministry entirely. Lee Do-hoon of Yonsei University in Seoul says South Korean government policies are still focused on men: “There needs to be policies that show that having and raising a child is just not entirely women’s responsibility.” Mr Yoon has instead blamed feminism for the country’s low fertility rate.

Japanese family law is outdated. Married couples cannot keep separate surnames, a practice the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has refused to change. (Women are the ones who change their names in 95% of cases.) Japan’s current minister in charge of children’s policies and female empowerment is Ogura Masanobu, a childless man perhaps best known for a stunt in which he and two other male lawmakers wore weighted jackets to simulate pregnancy for a day. Though many municipalities have pushed ahead and offered symbolic “partnership” certificates for same-sex couples, the national government has balked at legalising gay marriage. The LDP instead grudgingly passed a bill this month that offers gay people toothless protection against “unfair discrimination”, with no mention of marriage rights.

This will offer little succour to couples like Igarashi Hayato and Kanno Takafumi of Chiba, near Tokyo. The two men met on a dating app and registered their union through a local partnership system; they threw themselves a wedding themed around a favourite film, Disney’s “Little Mermaid”. They have long wanted children, but Japanese law has made it difficult; sperm and egg donations are restricted, and gay couples are often barred from adopting a foster child.

To get around these restrictions, the two came up with a highly unusual solution. They found a lesbian couple also keen to have children. The two pairs agreed to have two children together, with the women raising the first and the men the second. Mr Igarashi and Mr Kanno (pictured below) recently welcomed their baby and called her “Nanami”, which in Japanese contains the character for the ocean, in keeping with their family’s Little Mermaid theme. There is no legal framework to ensure they have custody – the mother has to abandon parental rights first. Then Mr Igarashi will adopt the child as a single father, and also adopt Mr Kanno as a second son, in order to ensure they all belong to the same family unit. “I guess politicians think there’s only one form of family,” Mr Igarashi laments. “They can’t imagine an alternative—they can’t imagine people like us exist and live in Japan.”

In many ways, public opinion has advanced further than political leaders. Polls show that a majority of Japanese, including a majority of LDP voters, support both legalising gay marriage and allowing couples to have separate surnames. Niinami Takeshi, the boss of Suntory, a Japanese beverage company, and the new head of Japan’s association of corporate executives, calls for greater understanding towards “the variety of ways of thinking about the life of a couple”. And although China’s central authorities promote a return to traditional gender roles, younger generations are increasingly open to wider roles for the genders and vocal about gender equality. Several recent incidents involving mistreatment of women have galvanised public anger in China: the case of a trafficked bride found chained by the neck in a rural man’s shed last year; or an incident caught on video of men thuggishly beating women who refused their advances at a restaurant.

Clinging to rigid family structures will intensify the demographic crunch, while constraining people’s ability to lead happy and free lives. Wiser policies would seek to better reflect the changing reality of modern families. “We need more flexible types of arrangements,” says Shirahase Sawako of the University of Tokyo. “If you rigidly design structures they degrade.” In particular, new structures must tackle the growing tension between well-educated, empowered women and the patriarchal social mores that still shape both private and public life in East Asia. Until that happens, women will continue pushing against the traditional roles of wife and mother—and in some cases, redefining what a family looks like.■

Photography by: SeongJoon Cho; Billy H.C. Kwok; Annabelle Chih; Noriko Hayashi