How Ukraine’s virtually non-existent navy sank Russia’s flagship

The Moskva was the most advanced vessel in the Black Sea. But the Ukrainians had a secret weapon, reports Wendell Steavenson with Marta Rodionova

July 27th 2023 • 25 min read

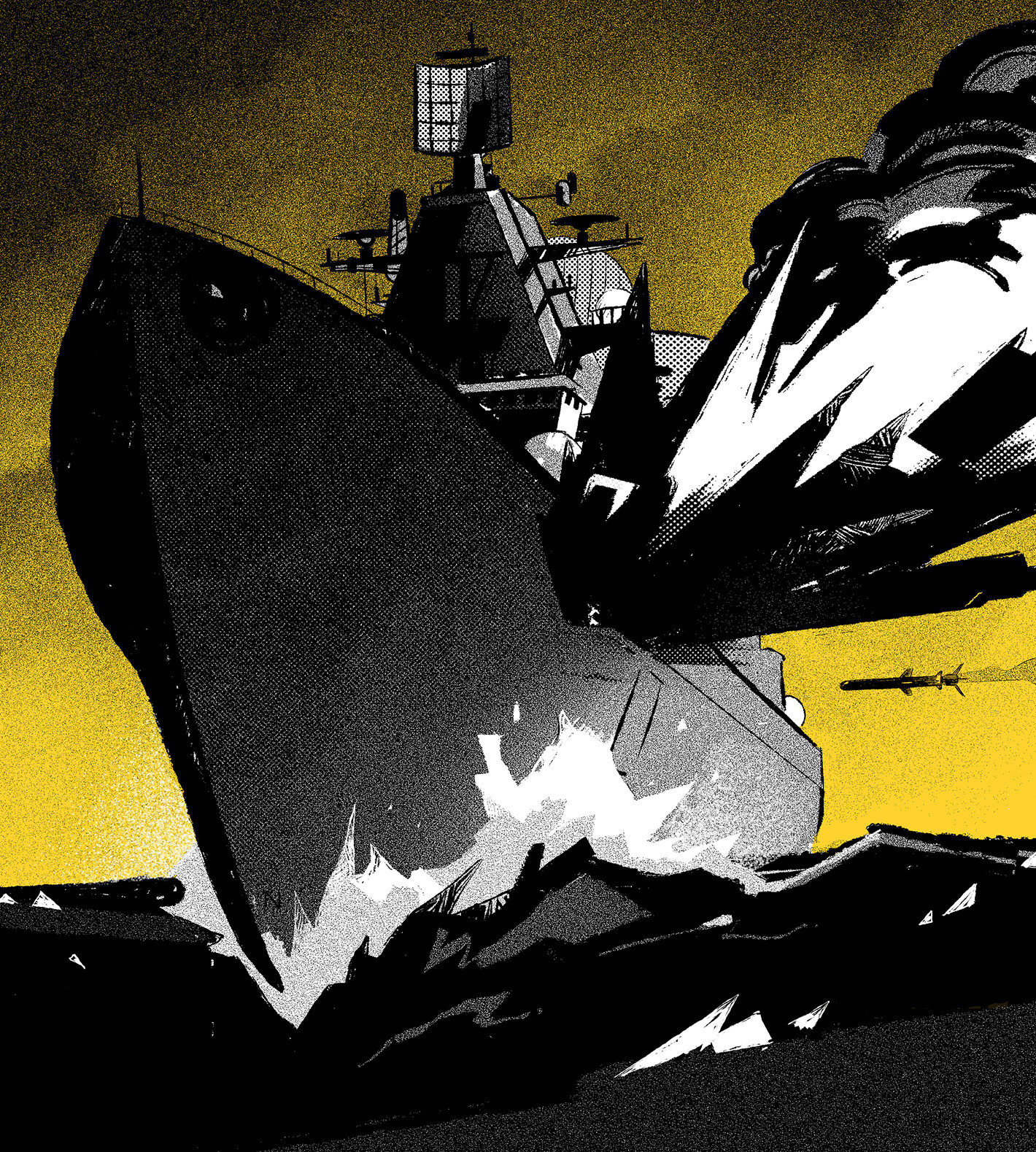

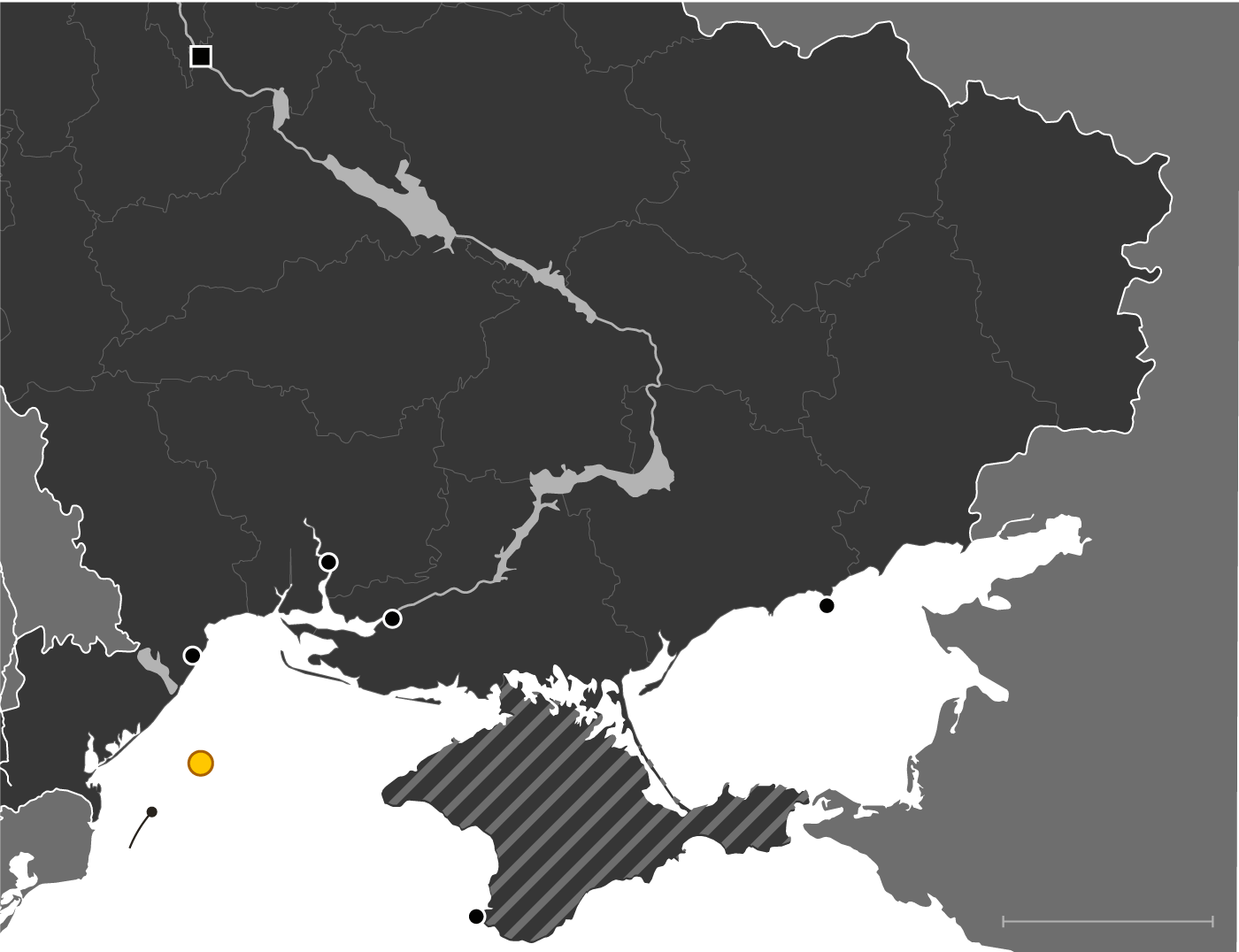

On the day that Russia invaded Ukraine, a flotilla of warships from the Russian Black Sea Fleet steamed out of its base in Sevastopol in occupied Crimea towards a small island 120km (75 miles) south of Odessa. This solitary speck of land, known as Snake Island, had strategic value beyond its size. If it were captured, the Russian navy would dominate the west of the Black Sea and threaten Ukraine’s coast. Snake Island housed a radar station and was garrisoned by a few dozen Ukrainian marines and border guards – no match for Russian ships.

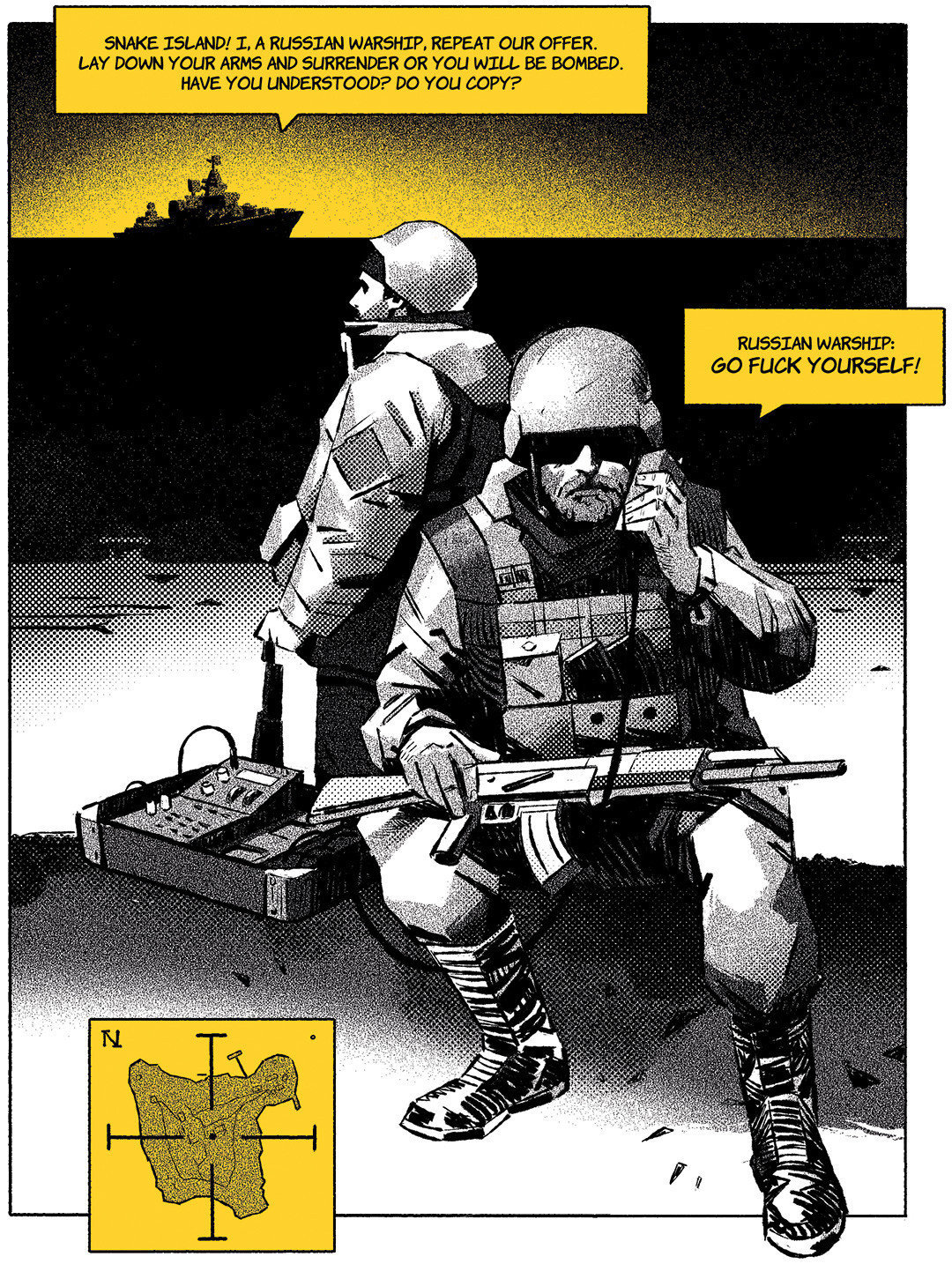

Russian jets screamed overhead. A patrol boat began shelling the island, and smaller vessels full of Russian marines approached the jetty. The Ukrainian defenders knew they had little hope of resisting. They were armed only with rifles and a few rocket-propelled grenades. Over the horizon appeared the great shadowing hulk of the Moskva, the Russian flagship, 186 metres long and bristling with missiles. It demanded over the radio that the garrison surrender.

“Snake Island! I, a Russian warship, repeat our offer. Lay down your arms and surrender or you will be bombed. Have you understood? Do you copy?” On a recording of the exchange, one Ukrainian border guard can be heard remarking to another: “Well, that’s it then – or should we reply that they should fuck off?” “Might as well,” said the second border guard. The first then uttered the riposte that would become a clarion call of Ukrainian resistance: “Russian warship, go fuck yourself!” The Russians stormed the island and all communications with the defenders were lost.

The following day, a medical team set off to the island to retrieve the bodies of the Ukrainian soldiers, all of whom they presumed were dead. As they approached, their rescue vessel was hailed by a Russian ship and ordered to stop. Soon, a dozen members of the Russian special forces boarded their boat and detained those on board. A Russian officer pointed over his shoulder at the dark grey outline of the Moskva in the distance. “Do you see her?” he said. “You see how large she is, how powerful? She can destroy not only Snake Island but all of Ukraine!”

“Do you see her?” he said. “You see how large she is, how powerful? She can destroy not only Snake Island but all of Ukraine!”

Meanwhile the Russian army advanced from Crimea westwards along Ukraine’s southern coast. Everyone expected that the Russian navy would support it with an amphibious landing, either in Mykolaiv, a naval base and shipyard that was now on the front line, or – the great prize – Odessa, which housed the headquarters of the Ukrainian navy. The navy mined possible landing zones. In Odessa volunteers filled sandbags and strung bales of barbed wire to defend the beaches. Russian warships appeared so close that people could see them on the horizon.

In Berdiansk, farther to the east, the Russians had captured a dozen Ukrainian ships. The Ukrainians didn’t want to risk any more falling into the hands of the enemy. With a heavy heart, Oleksiy Neizhpapa, the head of the Ukrainian navy, ordered the scuttling in Mykolaiv harbour of his two largest ships, including his flagship. “This is a difficult decision for any commander,” he told me. The Ukrainian navy was now reduced to around three dozen vessels, mostly patrol and supply boats.

Kyiv

Dnieper

UKRAINE

Mykolaiv

Berdiansk

Kherson

RUSSIA

Odessa

Sea of

Azov

Moskva sinks

Crimea

Black

Sea

Snake

Island

Sevastapol

150 km

Russian warships manoeuvred close to the coast, seeking to draw fire in order to make the Ukrainians reveal their artillery positions. Then they retreated out of range and targeted Ukrainian defences and command posts with missiles. The Moskva, the largest vessel of the Russian attack force, provided air cover which allowed the other ships to operate unmolested. Commercial shipping was throttled by the presence of Russia’s ships and mines. Ukraine, the fifth-largest exporter of wheat in the world, was unable to transport any grain.

Neizhpapa lost a number of officers and men in those perilous days. Crucially, though, radar installations, which allowed the Ukrainians to identify the position of Russian ships, escaped unharmed. Neizhpapa realised that he had one, untested weapon that might drive the Russian threat away from the coast. “We were counting on this being a factor of surprise for the enemy,” he said. “I was very worried that the enemy would know about it. After all, the enemy had a lot of agents on the territory of Ukraine. I was concerned about keeping it as secret as possible – and then, of course, using it.”

The Moskva, launched in 1983 under the name Slava, was one of three warships in her class to enter service. They were built in Mykolaiv in the last decade of the Soviet Union and designed to sink the ships of US navy carrier strike groups. Its American equivalent has a wider array of weapons but the Slava-class has missiles with a greater range, rendering her potentially more dangerous in a duel. The Soviet navy was proud of the Slava-class ships and sailors vied to serve on them. The cabins were comparatively large and there was a swimming pool in which the crew could decompress during the months at sea.

A messy process of disentangling naval assets began after Ukrainian independence. Russia and Ukraine divided the Soviet Black Sea Fleet between them. Russia got 80% of the ships, Ukraine 20%

The Soviet Black Sea Fleet, which welcomed the Moskva, also employed Neizhpapa’s father, who served as an officer on a rescue vessel. Neizhpapa himself was born in 1975 and grew up in Sevastopol. As a child, he drew pictures of warships and dreamed of becoming a sailor too. The Soviet Union was collapsing as Neizhpapa entered adulthood. He chose to stay in Sevastopol for naval school, rather than go to St Petersburg to study. Neizhpapa means “Don’t-eat-bread” in Cossack dialect. The name identified him as Ukrainian at a time when national identities were re-emerging. Ukraine became independent in 1991, and Neizhpapa was certain where his loyalties lay. “I realised that I did not want to serve Russia,” he said.

During Neizhpapa’s first year at naval school, Russians and Ukrainians studied together, but when the cadets were required to take an oath of allegiance, those who chose Russia left for training in St Petersburg. A messy process of disentangling naval assets also began after Ukrainian independence. Russia and Ukraine divided the Soviet Black Sea Fleet between them. Russia got 80% of the ships, Ukraine 20%. The two countries continued to share naval bases and there were even cases of brothers serving on different sides. Relations between the cohabiting fleets shifted according to the politics of the day, becoming more strained in the aftermath of Ukraine’s Orange revolution in 2004 and warmer when Viktor Yanukovych, a pro-Russian president, came to power in 2010. There were tensions over money – salaries in the Russian navy were much higher – and sometimes with the local authorities. (The Ukrainian police would let off Ukrainians for traffic violations but fine the Russians.)

In 2012 Neizhpapa, by then a captain, was invited on board the Moskva, which had become the flagship of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. He remembers the imposing size of the vessel, its foredeck canted upwards to attack. It was armed with 16 huge missile-launchers, as large as aircraft fuselages. The command tower was flanked with the domes, curved dishes and antennae of several radar systems, and the deck swooped towards a helicopter pad overhanging the stern.

When he stepped aboard, Neizhpapa “felt pride and tradition and also a certain power in the cruiser. I would have never guessed that within a couple of years my naval forces would sink it.”

On April 13th 2022, Neizhpapa received information that the Moskva had been located 115km off the coast. The vice admiral is tall and imposing with steel close-cut hair and bright blue eyes that seem to reflect some distant, sunny sea. Mild-mannered but military-correct, he would not be drawn on how the Ukrainians found the Moskva. “I can’t answer your question in much detail, but I can tell you that it was identified specifically by the Ukrainian naval forces,” he said.

It’s difficult to find warships at sea, not least because they are designed to hide. A ship can go quiet – turning off communications equipment so broadcasts cannot be intercepted – or use camouflage to make it difficult to see from above. Satellites can spot a ship only when their orbit passes overhead and most of them cannot penetrate cloud cover. Even when skies are clear, large warships are mere mites of grey on a vast grey ocean.

Most radar is limited to a range of 20-30km. It can transmit and receive electromagnetic pulses from objects only in its direct line of sight. Anything below the horizon remains invisible, in the radar’s so-called shadow. The Moskva remained on the other side of Snake Island, over 100km away.

Neizhpapa and other naval sources were understandably reluctant to furnish details on when and how they found the Moskva. According to their version of the story, low cloud cover that day meant that radar pulses were reflected in such a way that extended their reach far beyond their normal range. “The warship was found by two radar stations on the coast,” an insider told us. “We were so lucky.”

But Chris Carlson, a retired captain in the US navy and one of the designers of the naval-war game, “Harpoon V”, which is used to train armed forces around the world, believes that other methods were employed. “I have a hard time attributing it to just plain old luck,” he told me. He suggested that, even if a coastal radar station managed to ping the Moskva, the information relayed by the echo over such a distance would have been insufficient to identify the ship or target it effectively. Carlson pointed out that in 2021 Ukraine had announced that its advanced over-the-horizon radar system, called the Mineral-U, had completed factory testing. It’s possible that the navy rushed it into active service, even though the Ukrainians – given the need for wartime secrecy – have never admitted that they possess this capability. Neizhpapa said that this was not the first time the Ukrainians had spotted the Moskva and other warships.

Construction on the Moskva, initially called the Slava, started in 1976. The ship entered the Soviet Union’s navy in 1983. In 2000, after a decade of refitting, it became the flagship of the Russian navy’s Black Sea Fleet

At 186 metres long, two-thirds the length of the Titanic, the Moskva was the third-largest active ship in the Russian navy. It had a top speed of 32 knots (37mph)

In comparison with other Soviet-era ships, the Moskva was luxurious. Its crew – roughly 500 people – enjoyed relatively large cabins and even a swimming pool

Armed with a range of weapons, the Moskva’s upper deck was dominated by 16 anti-ship missile launchers for P-1000 Vulkan missiles

It came with three layers of protection. Distant threats could be addressed by eight S-300F surface-to-air missile launchers. Two OSA-MA launchers provided short-range cover. As a last ditch, six automated AK-630 gatling guns could fire a hail of bullets at anything that got too close.

On-board radars meanwhile could scan hundreds of kilometres beyond the ship and helped guide its anti-air missiles

source: janes, the economist

The Ukrainians had also deployed Bayraktars – Turkish-made drones that became cult icons in the early months of the war – against the Russian fleet for observation, distraction and attack. It’s possible that a drone may have spotted the Moskva. In private, Western military sources have hinted that the Ukrainians had more help in locating the Moskva than they like to admit. American military sources have confirmed that they were asked to verify Ukraine’s sighting of the Moskva, which they probably did through a maritime-surveillance aircraft. It was clear, however, from the predictable changes of position made by the Moskva, that her crew believed she was invisible.

The Ukrainian navy went into the war with a depleted force. After the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia seized much of the Ukrainian fleet, including 12 of the 17 ships moored in Sevastopol at the time. Training schools, artillery batteries and munition stores were claimed by the Russians. A cohort of Ukrainian naval officers, including three admirals, defected. Neizhpapa, who was at home in Sevastopol, was recalled to Odessa. He made it across the new de-facto border crammed into a car with his wife, two sons, the Ukrainian navy’s head of military communications and all the belongings they could fit. As they crossed to safety, Neizhpapa had a “feeling that I had been in captivity and was free at home”.

The Russians began to modernise their newly strengthened Black Sea Fleet; the Moskva was upgraded and ship-to-ship Vulkan missiles installed. These had a range of over 500km, which allowed them to target cities too. The Ukrainian fleet had been reduced to a handful of ships: one frigate and a few dozen smaller craft. The war in Donbas between the Ukrainian army and Russian-backed separatists stagnated into a stalemate and sucked up much of the armed forces’ attention and resources. When Neizhpapa was made commander of the navy in 2020 by President Volodymyr Zelensky, who had been elected the previous year, there was no money or time to build new ships. Neizhpapa decided that what he needed most of all were radar systems for surveillance, minefields for coastal defence and long-range missiles, which Ukraine had also lost in Crimea.

The Luch Design Bureau in Kyiv, a state-owned munitions developer since Soviet times, had begun work on the Neptune, a subsonic shore-to-ship missile system, shortly after the loss of Crimea. Based on an old Soviet design, the Neptune would have a range of over 200km. It was ready to be tested around the time Neizhpapa assumed command. A technical expert involved in the design, who didn’t want to be identified, showed me a video on his phone of one of the first live-fire tests. An old rusty tanker had been towed out to sea as a target and a small crowd of engineers and naval officers gathered in a field close to the launcher to await the results. When the news came that the tanker had been successfully hit, they clapped and hugged each other.

Yet the government dragged its feet on funding production and it took an intervention by Zelensky himself for manufacturing to begin. “I was in this meeting,” said the technical expert. “He was intelligent, he understood that we had only three or four [operationally effective] ships in the Ukrainian navy and that it was not enough to protect the coastline.”

Production began in early 2021. The first battery – comprising two command vehicles and four launch vehicles, each able to transport and fire four missiles – had been built in time to join the annual military parade in Kyiv on August 24th, Ukrainian Independence Day. That December, Neizhpapa announced that six batteries would be deployed to the southern coast the following spring.

On the morning of February 24th 2022, the technical expert woke to the sound of “shooting everywhere, helicopter attacks everywhere”. Russia had invaded and the Neptune batteries were still parked near Kyiv; they were in jeopardy from seizure by Russian soldiers. The technical expert’s superiors told him to transport the missile systems to the south of the country. It took three days for the launch vehicles to reach the coast. “We were worried because they were very visibly military vehicles,” said the expert. The missiles themselves were sent later, hidden in trucks.

The Neptunes were first fired in March 2022 at Russian landing craft. In April, they probably targeted a Russian frigate called the Admiral Essen – that month she was retired from service for a few weeks, suggesting that the damage sustained was slight – and at smaller ships threatening Mykolaiv. A number of sources suggested the Neptunes were not wholly successful. The system was untested in combat and there were teething problems: with the radar, with parts failing, with the software for identifying targets. The technical expert told us that the missiles had been launched from the west of Odessa at a high altitude, which would have made them more easily detectable by Russian radar. “We don’t know exactly what happened,” he said, “but it seems the missiles were intercepted.” Engineers were dispatched to fix the problems.

Once the location of the Moskva had been confirmed on April 13th, Neizhpapa ordered two Neptune missiles to be fired at it. The technical expert showed me a video on his phone of what he claimed was the launch of the missiles that day. The launcher truck was parked in a thin line of trees with bare branches. At ignition, the cap of the launching tube, which looks like the lid of a rubbish bin, was dispelled from the barrel and crashed into a field of green spring wheat. A fiery roar and a trail of black smoke followed. Then the second missile was launched.

A fiery roar and a trail of black smoke followed. Then the second missile was launched.

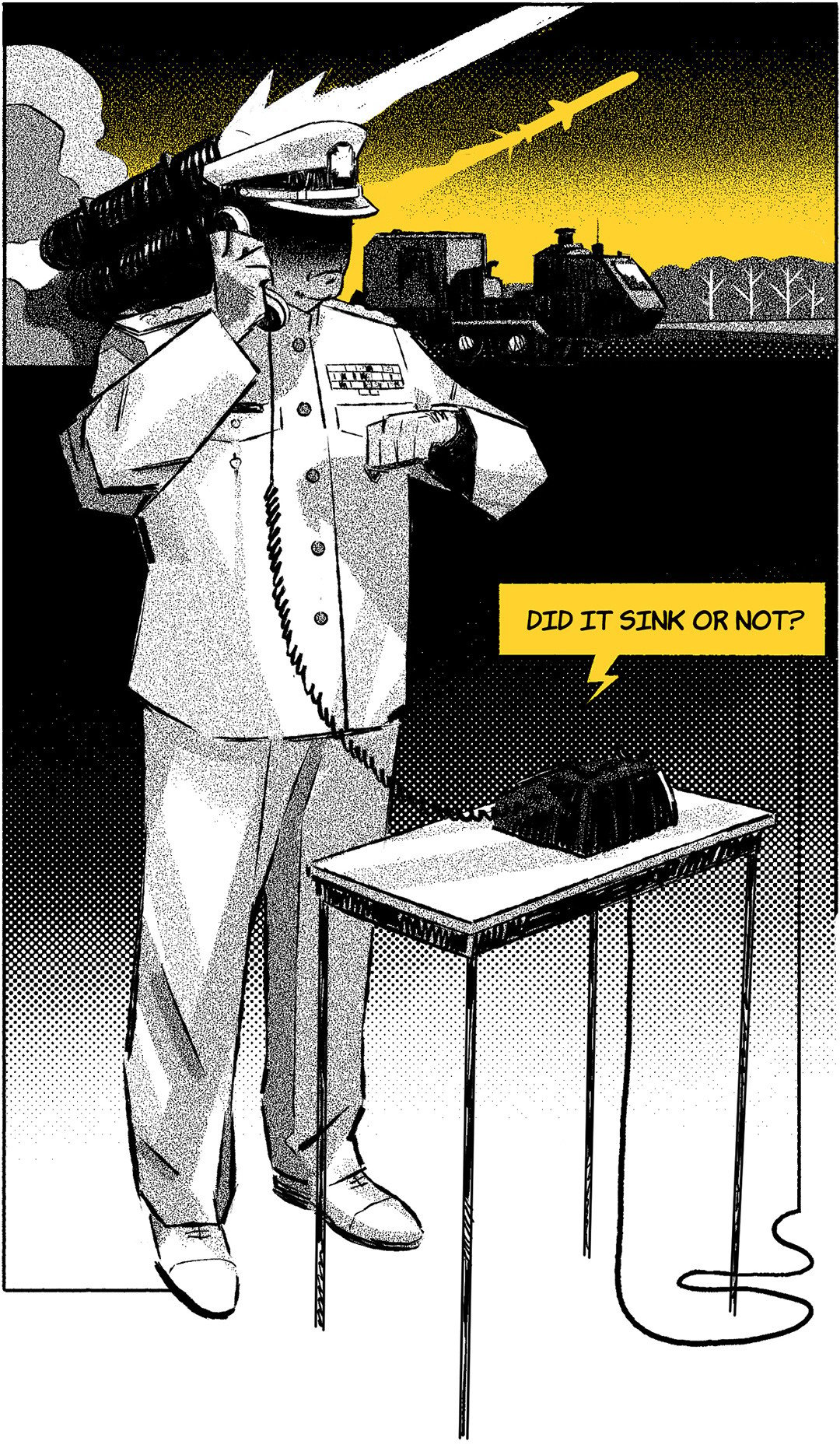

Silence reigned in Neizhpapa’s command centre. The Neptune, which is five metres long, flies at 900km per hour and is designed to skim ten metres above the surface of the sea in order to avoid detection. Neizhpapa watched the clock tick through the six minutes that it was supposed to take to reach the target. For a long time nothing seemed to happen. Then Russian radio channels erupted in chatter. It was apparent that smaller ships were hurrying towards the Moskva. The radio traffic was garbled and panicked. Neizhpapa inferred that the ship had been hit.

It didn’t take long for news to spread. “People started calling me from all over Ukraine,” Neizhpapa said. “There was only one question: ‘Did it sink or not?’ I said, ‘I can’t answer that!’ Hours passed. I was constantly asked the same thing. I joked I wanted to get on a boat myself and go and look. I said, ‘Do you realise that this is a very big ship? Even if it was hit by both missiles, it wouldn’t sink immediately.’”

The Ukrainians developed the Neptune subsonic anti-ship cruise missile shortly after the Russians invaded Crimea in 2014. It was based on the design of the Kh-35, a Soviet-era cruise missile

The Neptune is five metres long, flies at more than 500mph and skims ten metres above the surface of the waves to avoid detection

Its warhead weighs 150 kilograms

With a range of more than 300km, it is powered by a specially built MS-400 turbofan engine

source: janes, the economist

Some hours later, satellites spotted a large red thermal image in the middle of the sea. Officials from NATO phoned Neizhpapa, he recalled, “to say that they saw something burning beautifully”.

The only publicly available film taken of the Moskva after she was hit is three seconds long. The sea is calm, the sky pale grey. The full length of the ship is visible as she lists sharply to one side, thick black smoke billowing from the foredeck. Her life rafts are gone, suggesting that surviving crew members had been evacuated. The camera falls away sharply as a voice is heard saying, in Russian, “What the fuck are you doing?”

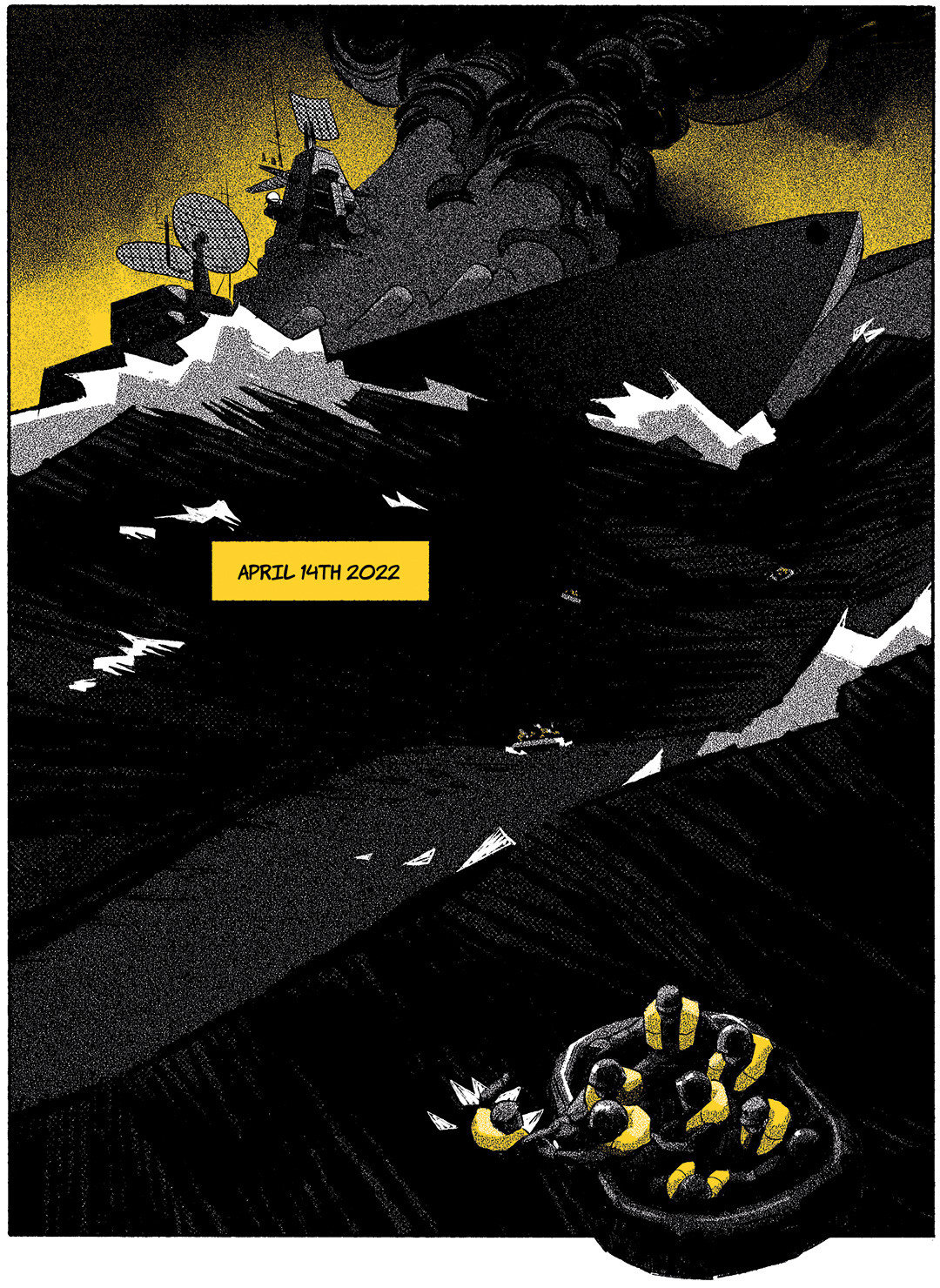

It’s apparent from the film that the two Neptune missiles struck the Moskva near the foredeck on her port side, just above the waterline. The fire may have been caused by the missiles themselves, or fuel tanks or ammunition magazines in that part of the ship which ignited. We may never know exactly what happened but the attack clearly caused the Moskva to lose power and propulsion. Sometime in the early hours of April 14th she rolled over and sank.

Why had the Moskva, which had capable radar and surface-to-air missiles, failed to detect and intercept the incoming Neptunes? Carlson, the naval expert, has dug into the possible reasons. The ship was in dry dock for repairs several times over the past decade but upgrades to her weapons and operating systems seem to have been delayed or done piecemeal. A readiness report, briefly posted online in early 2022 before being removed from the internet, showed that many systems were broken or not fully functional. “All her major weapons systems had gripes,” said Carlson on a podcast last year. Moreover, the Moskva’s radar and targeting tools were not entirely automated and relied heavily on well-trained operators. But over half the ship’s crew, which numbered 500, were conscripts who served only a year. In consequence, the sailors “had extremely limited training which would be considered woefully insufficient by Western standards,” said Carlson. “The Moskva was not properly prepared to be doing combat operations.” This was yet another example of complacency by the Russian armed forces that has been evident throughout the war. Even so, Carlson was astonished that none of her radars appeared to have spotted the incoming missiles.

Officials from NATO phoned Neizhpapa, he recalled, “to say that they saw something burning beautifully

Once the Neptunes struck, the crew seems, in a panic, to have left watertight doors unsecured. Studying a screenshot of the Moskva on fire, Carlson observed that “you can see smoke coming out of the shutter doors for the torpedo tubes...That tells me that the smoke had a clear path, and if the smoke had a clear path so did water and so [did] flame.”

The Russians have never admitted that Neptune missiles were responsible for sinking the Moskva; they claimed she suffered an accidental fire at sea. But only a few days later, they bombed a Luch Design Bureau facility in Kyiv in apparent retaliation. The Russian authorities have also never been open about the number of casualties, but up to 250 sailors may have died. On November 4th 2022, more than six months after the sinking, a court in Sevastopol declared 17 of the missing dead.

Despite the reports of their heroic deaths, the defenders of Snake Island were in fact alive. They were taken captive and held in prison in Crimea before being transferred to a prison in Belograd, a city near the border with Ukraine. Conditions were brutal. Temperatures fell to -20°C, yet the prisoners were housed in tents for the first few days. Frequently, they were interrogated, beaten and electrocuted. They had no news of the outside world, beyond the names of the cities captured by the Russians, with which the guards taunted them.

One day, the prisoners overheard a news report on the guards’ radio saying that the Moskva “was not floating properly”. The expression puzzled them for a while, before they realised that it was a euphemism for “sunk”. They began to cheer. “The Russians increased our torture,” said one of them, who was later returned in a prisoner exchange, “but this was a great moment of happiness.”

The sinking of the Moskva was a turning point in the war. Neizhpapa said that “our fleet, which was considered non-existent a year ago, is now winning against the larger force, thought to be unbeatable.” NATO allies began to take the Ukrainian navy seriously. Ukraine has limited stocks of Neptunes but the Danes and Americans are supplying Harpoon missiles, which are similar to the Neptune but carry a bigger warhead. Previously, Neizhpapa admitted, this kind of weapon and support would have been a “dream”.

Sometime in the early hours of April 14th she rolled over and sank.

Having destroyed the air-defence umbrella that the Moskva provided, the Ukrainian navy was able to harass the Russian navy in the west of the Black Sea with drones and missiles, damaging and sinking supply ships, and destroying air defences and radar stations installed on gas platforms. In June 2022 Ukraine retook Snake Island and the Russian Black Sea Fleet withdrew towards Crimea, leaving the Ukrainian coast safe from amphibious assault. Turkey and the United Nations were able to broker a deal to allow ships into Ukrainian ports to export grain. “Now,” said Neizhpapa, “they keep their ships outside of the range of our cruise missiles” – even state-of-the-art frigates that are armed up to the gunwales.

The Ukrainian coast has been secured. Neizhpapa pointed out an area of 25,000 square kilometres where neither the Russians nor Ukrainians can now operate freely. “There’s a certain kind of status quo that we need to take over,” he said. Neizhpapa maintains that the only way to secure peace in the Black Sea is to throw the Russians out of Crimea. “In imperial times, all of the emperors always said that whoever controls Crimea controls the Black Sea. In Soviet times, they called Crimea the aircraft-carrier that cannot be sunk. Nothing has changed since then.”

I asked Neizhpapa what he missed about his home. He gazed upwards for a moment. “Honestly, I miss the sea near Crimea the most. It’s not the same as here. It’s brighter, more transparent.” ■

Wendell Steavenson has reported on post-Soviet Georgia, the Iraq war and the Egyptian revolution. You can read her previous dispatches from the war in Ukraine for 1843 magazine, and the rest of our coverage here. Marta Rodionova has worked as a television journalist and creative producer.

Illustrations: Coke Navarro